We spend our lives learning, failing and trying again when it comes to money. Most of us are able to get to a place where we can make it work. There are different advantages, various mistakes. How we get to that place of financial understanding can be gradual and a bit of a mystery, kind of like compound interest.

Teenagers meet money at the crossroads of their own adulthood. So, in teaching about financial literacy, we have a fascinating view of what teenagers have found out, were never taught, don’t quite get and would love more information on.

Teenagers meet money at the crossroads of their own adulthood. So, in teaching about financial literacy, we have a fascinating view of what teenagers have found out, were never taught, don’t quite get and would love more information on.

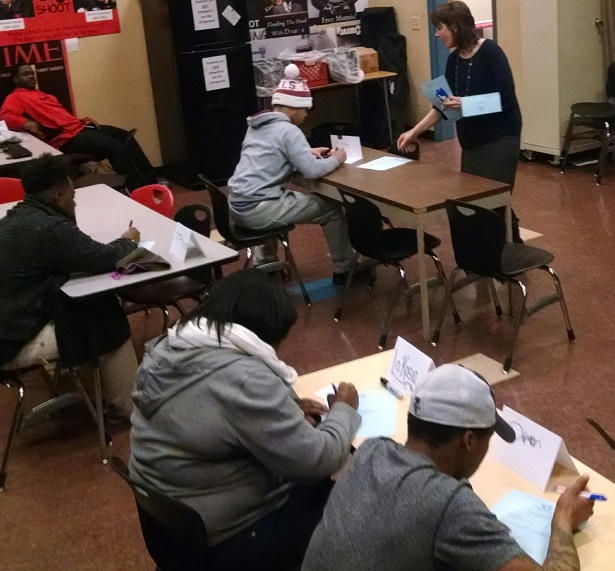

Our hundreds of Money Sense classes run throughout the school year. On Wednesday, we held our first Money Sense lesson at Transition High School, located in a commercial strip along North Avenue near Fond du Lac Avenue. Transition is part of Milwaukee Public Schools and works with students returning from expulsion or incarceration on specialized learning plans and personal growth. The school has a wide-open floor plan with students bouncing between computers and side meeting rooms of varying size for certain classes or presentations. Our Money Sense lesson was in a meeting room with high ceilings, made larger by the monumental historical figures and artists on posters that covered every inch of the walls – Martin Luther King Jr., Huey Newton, Public Enemy, characters from “The Wire”. On a frozen day outdoors, the student body inside Transition was a welcome pocket of activity.

As the class started, students began to open up – some more than others – about their understanding of money. One obvious interaction they have with cash comes from those first jobs. Tramond helps out at a day care. Stan has a job in fast food and concessions at Miller Park. Damari, 17, peering at the paycheck example on the projector screen during the classroom exercise, said: “I need to get a job.”

Damari doesn’t have a job right now. He does, on the other hand, have a hankering for burgers and French fries. This hunger has taken a bite out of his pocketbook. In talking over with the whole class about spending habits, Damari made an instant connection to his fast food finances.

“I can eliminate irrelevant expenses. Fast food could be one thing

Ryan, 17 in a Chicago Bulls beanie, knew his financial history. He nailed down the date of the Great Depression and spotted the ways Baby Boomers might impact FICA on a paycheck.

La Kasia, a student and a mother, was ebullient and eager to chime in on lesson questions. Already so vested in the adult world, La Kasia had a detailed understanding of every dollar in her budget, even if it’s sometimes in the red. She’s looking forward to earning her diploma and has daydreams about planning a trip to Hawaii. (“I’d want to go there for my birthday.”) When walking through the deductions from a sample paycheck in our lesson, she joked about hitting up her retired father for the part of Social Security she’s paying into with her two part-time jobs.

“So, technically, I should ask my dad for that $7 back?” she said, laughing.

As the class neared the bell, the students were given an offer. Lesson leader Brenda Campbell – also our organization’s President and CEO, who leads a class at Transition every year – asked each of the teens if they’d rather have one gold chocolate “coin” now, or five gold chocolate coins next week? This is on par with the famed Stanford experiment with young children and tasty marshmallows that sought to better explain delayed gratification (as seen in this video). For our purposes, the same idea fits when it comes to budgeting, spending and saving.

Each Transition student heard Brenda’s pitch – one gold chocolate coin right now … or five at next week’s class. Some students paused, others answered right away, all checking out the candy reward during their response. Every student said they’d wait for the bigger return of five coins at next week’s class.

-by Justin Kern, Marketing and Communications Manager, Make A Difference – Wisconsin